When Granite Was King

- by Chris Stewart

- Oct 16, 1981

- 7 min read

Harry Mason Recalled Redstone’s Glory Days

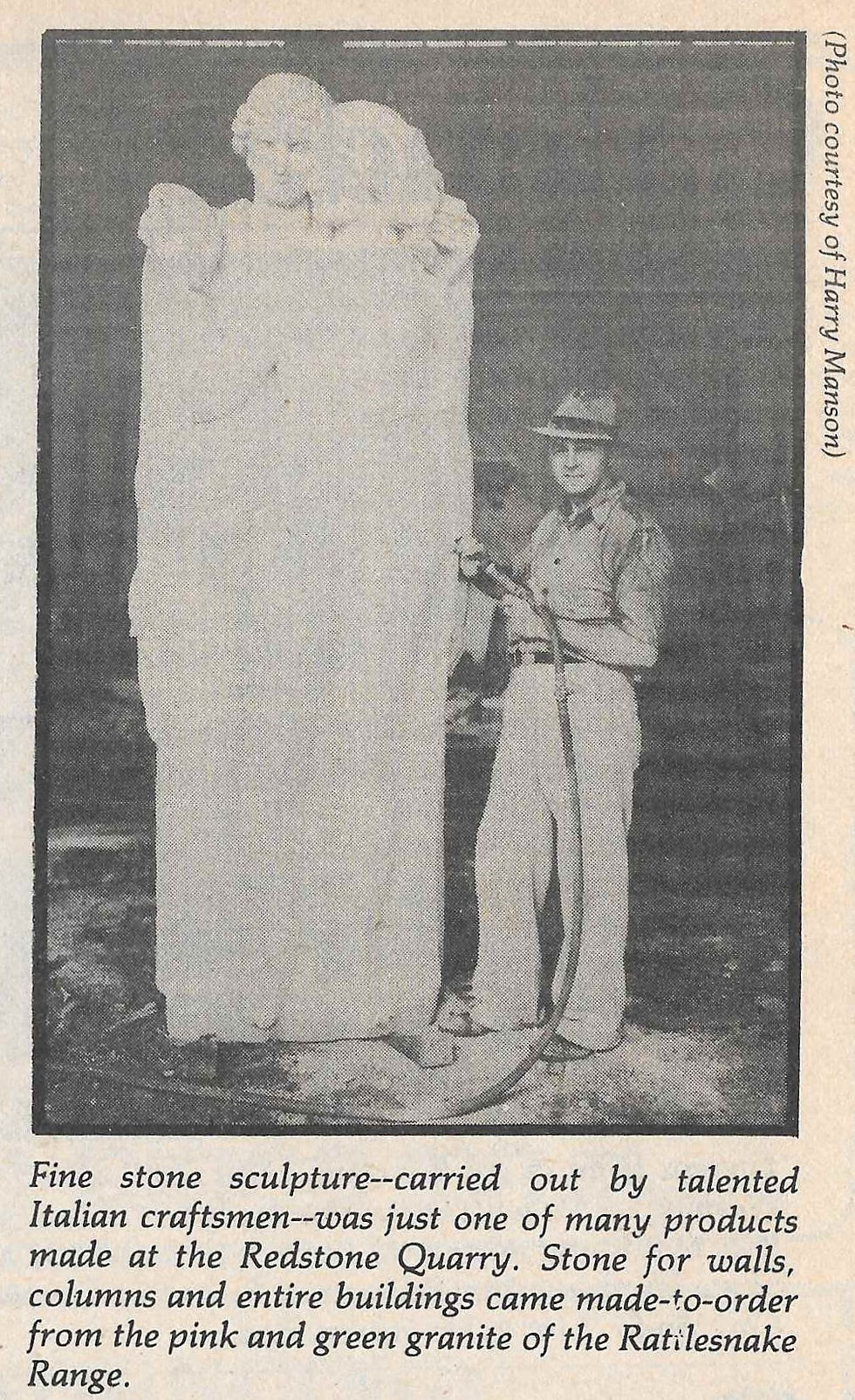

Editor's Note: This is an article written by Chris Stewart in 1981 — now of Portland, Maine — who interviewed then 83-year-old local stone mason Harry Mason about his memories of working in Redstone, when granite was king. Mason passed away in 1985. The article provides some of the rich history of the Redstone Quarry.

When think of the Mt. Washington Valley, the first thing that comes to mind isn’t giant slabs of granite being hoisted from the Redstone quarry.

Today the region is better known as a four-season resort where skiers, hikers, campers, tourists and others congregate during their vacations. Incoming travelers on Route 302 passing through the quiet village of Redstone rarely notice the sheer exposed rock walls still visible from the highway.

At the turn of the 20th century, however, at the Redstone southern edge of the Rattlesnake Range, as many as 350 men once labored to quarry, cut, haul and polish the plentiful lode of green and pink granite. The work these men carried out put Conway on the map.

Conway granite from Redstone was used in buildings as far away as Havana, Cuba; New Orleans, Detroit, Chicago and Denver, and it is part of such well known structures as Philadelphia’s Fidelity Trust, the Mellon Institute in Pittsburgh, New York City’s Curb Exchange Building and the Houghton-Dutton Block in Boston.

Harry Mason clearly remembered the way it was. Born and raised in East Conway, Harry first started to work for the Maine and New Hampshire Granite Company — owners of the quarry — in 1913. He was 17 years old.

During the next 28 years, Harry worked in several different jobs, starting out by carrying tools, and soon advancing to become a jackhammer operator, then derrick operator and finally the derrick foreman, a post he held for 15 years.

As Harry noted, the Redstone quarry was known not only for its quality stone, but for its unusual formation as well.

“We had two quarries,” he explained, “with pink granite on the western side and green granite on the east.”

Between these two formations, a narrow band of “heading,” 20 to 50 feet wide, ran almost directly north and south, separating the rocks. From 1882 until the early years of World War II, the operation at Redstone moved further into the mountain each year.

By the time he started, Harry recalled that a thriving community had grown up around the quarry. Twenty-two houses, a store, a bowling alley, and a boarding house had already been constructed, and — by 1910 — a half-mile-long railroad spur led from inside the “stone” shed to the Maine Central Railroad’s tracks. From inside the 400-foot-long “stone” shed, the granite was cut, polished and loaded onto flatbed cars for shipment. The “stone” shed also housed modern compression equipment, machines which reduced the size of the quarry’s workforce.

“During the years when I was working, there might be as many as 250 men at the quarry when they had a big job to do,” Harry said. “But in the early years, before they had air-powered tools — and all the work was done by hand — they employed 300 or more men at a time.”

These labor saving tools — first introduced in 1904 — included powered jackhammers, four- and six-point “flatteners” (stone pounding machines), cranes, and giant lathes. “After they brought in that first boiler and air compressor, they added another one in 1906,” Harry continued. “[In 1979], the company sold the boiler doors and they’re now in a museum in Augusta, Maine. The oldest derrick and some castings are there, too.”

Although the introduction of these machines eased the physical labor of cutting the stone, the work was taxing.

Turning these giant slabs into usable stone proved equally difficult. This task fell to the stone cutters who — until 1924 — used chisels and other hand tools to achieve the desired shape through long hours of patient work.

While orders for paving stones from New York City, Portland and elsewhere kept the cutters busy, the demand for more finely cut rock resulted in the introduction of mechanized stone saws in 1924. Like the mechanized jackhammer, the stone saws greatly improved the quarry’s efficiency.

“Before a slab went into the shed it was cut as close as possible to size,” Harry said. “Then the stone cutters would cut it to a more exact size.”

Since the stones were often large — sometimes eight by three by six feet —and heavy (weighing approximately 150 pounds a cubic foot), each stage in processing a stone took time. Finally, if needed, the cut stone would be smoothed by the polishing wheels which were also located in the “stone” shed. Varying in size from a foot to three and a half feet in diameter, the electric-driven polishing wheels were the last step before a stone was shipped out by rail.

Long before gondolas and tramways became popular at New Hampshire’s ski areas, the Redstone quarry had a lift of its own, though it was employed for a far different purpose.

To bring the pink granite down from the eastern quarry, a clever system of cable cars was constructed. Running on a continuous steel cable, platforms circulated between the ledges and the “stone” shed, carrying granite downhill and bringing coal (to power the jackhammers and derricks) back uphill in one flowing motion. A brake drum mechanism known as a “crab” governed the speed that the cars moved, and Harry often found himself at the controls.

“You had to carefully estimate the size of the stone going downhill with the size of the load going up,” he recalled. “If you had nothing to send uphill, you had to ease the load down very slowly, but if you had six or seven tons of coal to balance the load, you could ease off the brakes.”

Too much braking might mean that the cars would stall, while too little pressure on the “crab” would let the stone speed downhill and out of control.

Though the increased efficiency resulting from the stone saws had further cut back the quarry workforce to 150 men, Harry pointed out that the demand for Redstone granite reached its high point just before the early 1930s.

Among all the projects carried out during this time, he remembered the work on the Masonic Temple in Alexandria, Va., as being one of the most challenging. Part of the order from the Temple called for two dozen columns of green granite, each to be 22 feet long and three and a half feet wide. A single one weighed 18 tons.

“I helped quarry them out,” Harry said. “In fact, I used to go down to the ‘stone’ shed and set them in the turning lathe. We had one lathe for turning them and another for polishing. The stone cutters roughed them out and helped put them in the lathe, but they had to be as round as they could be before we set them in the lathe.”

With hand powered pressure, rough pads wore against the stone, shaping it slowly — one column at a time — into form.

“We started in on that project on the fifth day of February, 1923, and we didn’t finish with it until the end of 1923,” Harry recalled.

Part of the reason it took so long was a result of the painstaking work required, but part of the reason was the result of the demand for stone from other projects.

“At the same time we were doing the Temple, we had two or three different large jobs to complete,” Harry continued.

Among those projects was the Archives Building in Washington, D.C., a structure finished in 1930.

In the 1930s, while most Americans suffered through hard economic times, Redstone enjoyed nearly full employment.

“Around here, during those years, we didn’t know what the Depression was,” Harry explained. “We were always busy.”

Even though the quarry experienced the setback of having the “stone” shed burn, it was quickly replaced with a fireproof steel structure the following year and work continued apace.

“During that time we built the Hatch Memorial in Boston,” he added. “Every mite of that stone came from here.”

Unfortunately, though the Redstone quarry escaped the Depression, it could not elude the changing technology, consumer habits and needs of America in the 1940s.

The quarry’s new owners operated other quarries more modern than Redstone where rock could be processed at far less cost.

Increases in freight charges for shipping the granite, coupled with a growing preference for limestone and cement in place of granite — “a lot of people used it because it was cheaper” — also hurt business.

More serious, however, was the declining accessibility of good granite.

“The stone just ran out,” Harry said. “We had to go further and further back into the mountain, and we found only poor quality stone.”

Increasingly, quarrymen had discovered that the stone was cracked, full of seams, and “striped” (impure), trends which reduced the percentage of usable stone quarried to 55. Before this time, about 80 percent of the stone had been usable.

“The costs for operating were fixed,” he explained, “and it costs just as much to quarry the bad rock as the good rock. We just couldn’t afford to do it any longer.”

At the beginning of the War, General Electric bought the new shed, tore it down and moved it to Lynn, Mass.

Though the quarry operation closed down, Harry continued to keep busy with farming, logging and quarry work on his own, cutting wall stone, landmarks for surveyors, and fireplace stone.

Many of the stone bases around the larger Forest Service signs along the highways in the White Mountain National Forest are examples of his work.

Afterward, he lived with his wife Ruth in Redstone, where he kept busy. At the age of 83, he remained the quarry’s caretaker, even though there was no hope that the quarry would re-open.

At the time Harry said, “today they’re doing as much work as they ever did with granite. They’re using it for cribbing along roads and everything else. I sure miss the old quarry!”